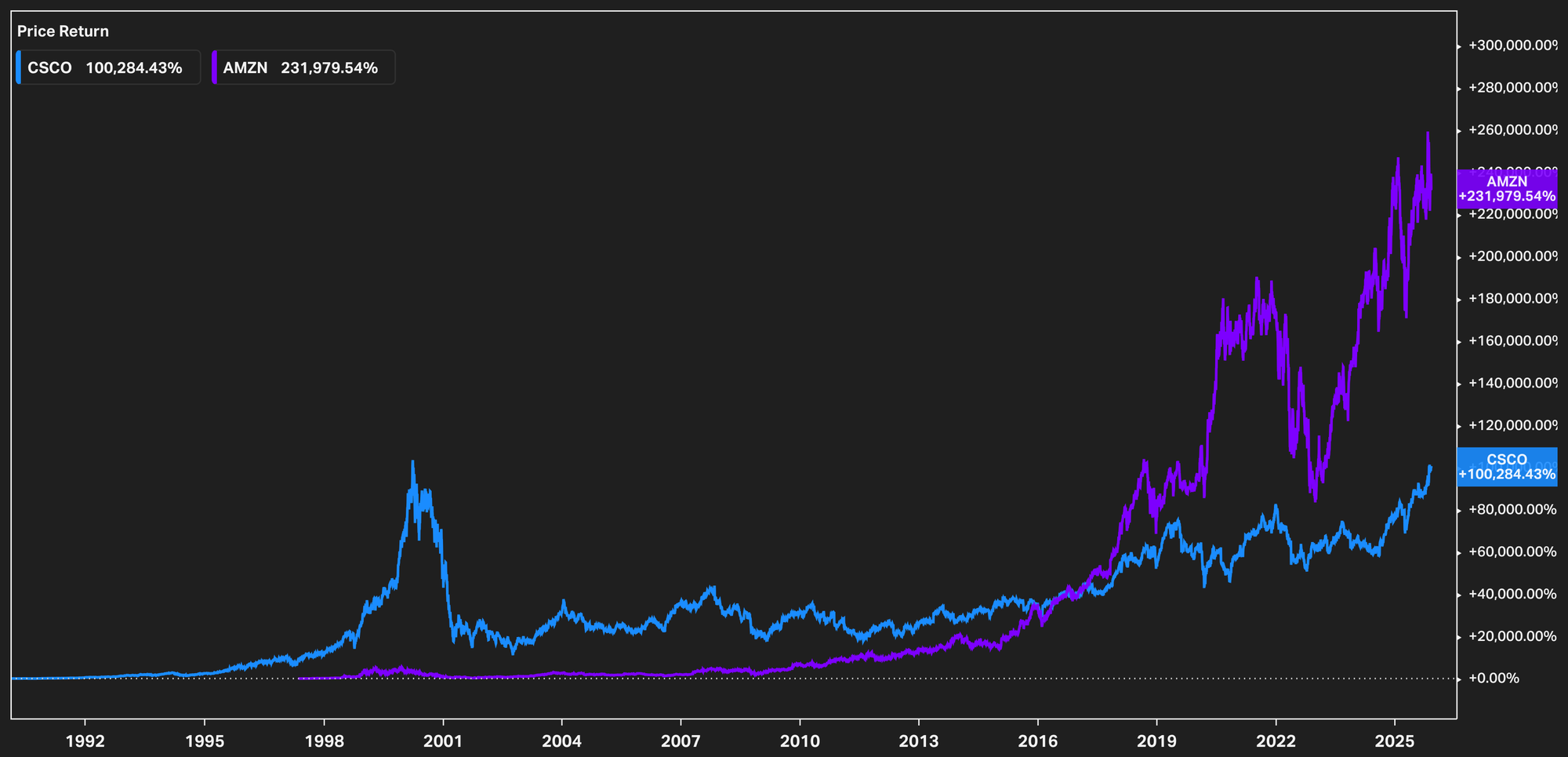

In March 2000, Cisco Systems briefly became the most valuable company in the world with a market cap of $555 billion. The networking equipment maker was selling picks and shovels for the internet gold rush. The logic was airtight: more internet traffic meant more routers and switches, forever.

Twenty-five years later, Cisco trades at $305 billion. The company remained profitable, paid dividends, and stayed relevant. But investors who bought at the peak lost money even before inflation.

Meanwhile, Amazon collapsed 95% from December 1999 to September 2001. The company nearly ran out of cash. Analysts questioned whether it would survive. Today it's worth over $2 trillion. Peak buyers made 20x.

This isn't random. It's the pattern that Carlota Perez spent decades documenting across technological revolutions. The companies that look like obvious winners during the infrastructure build-out often underperform over the full cycle. The companies that look shaky or boring during the build-out often generate the highest long-term returns.

Understanding why requires grasping that general-purpose technologies unfold in two distinct phases that reward completely different behaviors, different companies, and different investor types.

Installation builds capacity, deployment extracts value

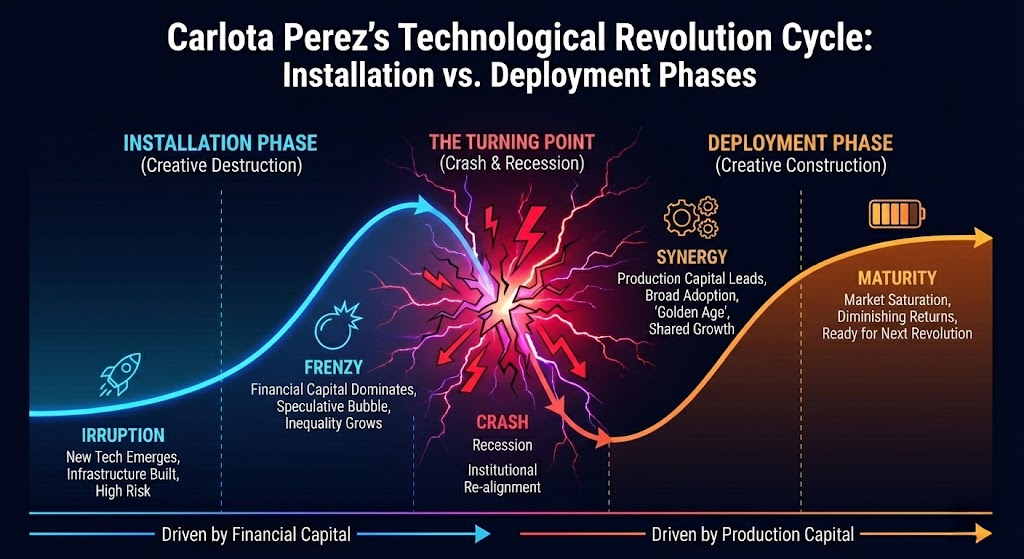

Perez's core insight is deceptively simple. Every major technological revolution splits into two phases with fundamentally different dynamics.

Installation is finance-led. Capital floods into building infrastructure. New companies form rapidly. Stock prices disconnect from cash flows. The focus is on growth, market share, and positioning. Success means building capacity faster than competitors. The question everyone asks is "how big will this get?"

Deployment is production-led. The infrastructure gets put to productive use. Business models crystallize. Profit margins matter. Success means extracting value from capacity that already exists. The question shifts to "how do we make money from this?"

The transition between phases is marked by what Perez calls the turning point, typically a crash or sharp correction. The dot-com crash was the turning point for internet infrastructure. The 2008 crisis played that role for the broader digital economy. These aren't accidents or market failures. They're features of the process, the mechanism that forces collective reassessment of what the infrastructure is actually worth.

Here's the part most investors miss: these phases don't just reward different strategies. They reward different types of people. Installation rewards traders, dealmakers, and risk-takers who can play the momentum game. Deployment rewards operators, integrators, and capital allocators who can compound cash flows.

Venture capital exists to exploit installation phase dynamics. VCs fund capacity building, price companies based on growth trajectories and exit multiples, and sell before deployment begins. The entire model works because installation phase pricing disconnects from fundamentals, creating an arbitrage between what VCs pay and what later investors will pay.

The best VC vintages are deployed during or shortly after corrections, when infrastructure build-out is accelerating but valuations have reset. The worst vintages are deployed at peak installation, when capital is abundant and everyone extrapolates exponential growth. Notice the timing: VCs exit during late installation or early deployment, selling to growth equity, who sell to public markets.

Public equity investors who chase growth stocks during installation are playing the same game as VCs but with worse information, worse access, worse terms, and no contractual protections. They're paying deployment prices for installation risk.

The games we play

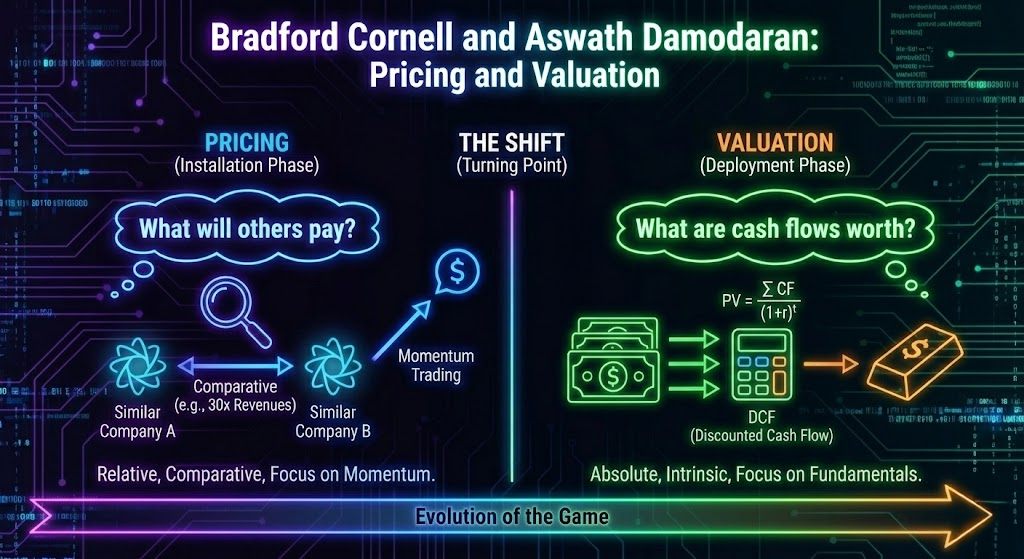

Bradford Cornell and Aswath Damodaran describe this from a valuation angle. They distinguish between pricing and valuation as fundamentally different exercises.

Pricing is comparative. You look at what others pay for similar companies and price accordingly. If AI infrastructure companies trade at 30x revenues, your AI infrastructure startup should trade at 30x revenues, adjusted for growth and market position. The entire exercise is relative. You're not asking what the company is intrinsically worth. You're asking what others will pay.

Valuation is absolute. You forecast cash flows, estimate risk, discount to present value. You can't hide behind comparables. The math either works or it doesn't.

During installation, Cornell and Damodaran say markets are "all pricing, all the time." Fundamentals are unknowable, so investors stop trying to know them. They play momentum, buying what they think others will pay more for tomorrow. This can continue for years.

During deployment, valuation reasserts itself. Companies that looked cheap on growth expectations but expensive on fundamentals get repriced down. Companies that looked expensive on growth but reasonable on cash flows start compounding. The game changes from "what will someone pay" to "what are the cash flows worth."

Public equity alpha in general-purpose technologies skews much later than people think.

The spectacular returns during installation accrue primarily to early-stage investors who can exit before the turning point. Public market investors who chase installation-phase winners often buy high and watch gains evaporate during the transition. The durable public equity returns come during deployment, from companies that figured out how to profitably use infrastructure that others built.

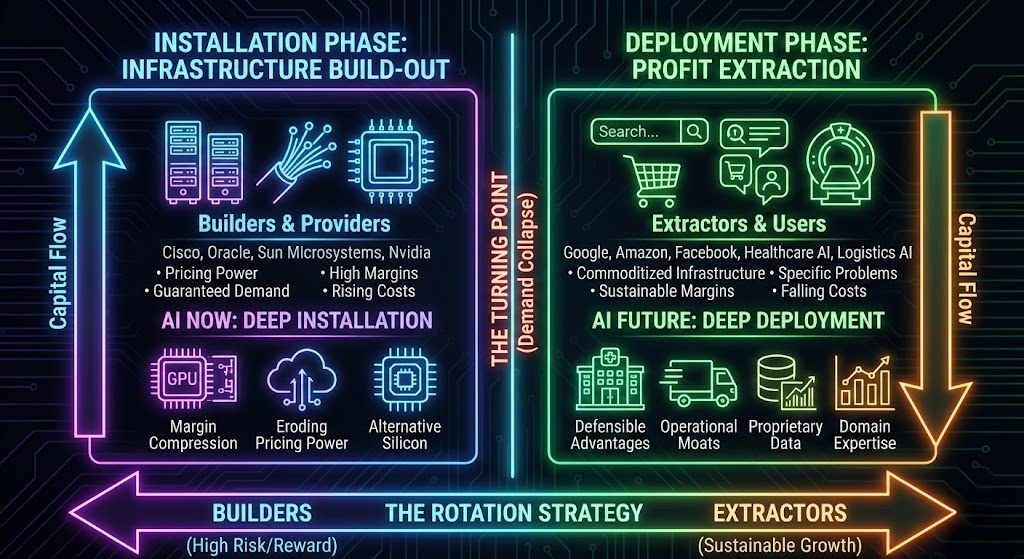

The rotation strategy

During internet installation, the winning trade was owning Cisco, Oracle, and Sun Microsystems. These companies had pricing power, high margins, and guaranteed demand as long as build-out continued.

When installation ended, demand stopped. Customers already had infrastructure and started sweating those assets. Capital expenditure budgets collapsed. Pricing power evaporated. Growth halted.

A different set of companies thrived during deployment. Google monetized search using advertising infrastructure others built. Amazon dominated e-commerce using logistics infrastructure others funded. Facebook built social networks on internet infrastructure already in place. These companies didn't build the internet. They extracted profits from it.

Notice what deployment winners have in common. They're using commoditized infrastructure to solve specific problems in ways that generate sustainable margins. They're often in industries that look boring or traditional. They benefit from infrastructure costs falling, not rising. And they're frequently not the companies that dominated installation-phase headlines.

For AI, we're deep in installation. Every signal confirms it. But the deployment rotation will come, and when it does, the playbook is clear even if the specific companies aren't.

The infrastructure builders will face margin compression. Nvidia's pricing power erodes as AMD, Intel, and hyperscaler custom silicon provide alternatives. The neo-clouds face pressure as AWS and Azure add specialized AI capabilities. The companies racing to build capacity discover their customers enter digestion mode.

The deployment winners will be companies using AI infrastructure to create defensible business advantages. A healthcare company that uses AI to reduce diagnostic costs by 60% while improving accuracy. A logistics company that optimizes routing to cut fuel consumption 20%. A financial services firm that underwrites risk better than competitors using models trained on proprietary data.

These aren't headline stories during installation. They're operational stories. They're businesses solving specific problems in specific industries using tools that are becoming commoditized. The moats aren't the AI. The moats are the data, the workflows, the customer relationships, the domain expertise.

What to watch for

The challenge is timing the rotation. Installation can run longer than seems rational when deep-pocketed hyperscalers have decade-long horizons. And turning points are triggered by narrative shifts, not fundamental changes.

Cornell and Damodaran document this across their case studies. The dot-com crash in March 2000 wasn't triggered by specific earnings disappointments. The facts were mostly known. What changed was the collective story investors told about those facts. The cannabis collapse in 2019 happened even though underlying market opportunity hadn't changed. The narrative flipped from "massive growth ahead" to "maybe this takes longer."

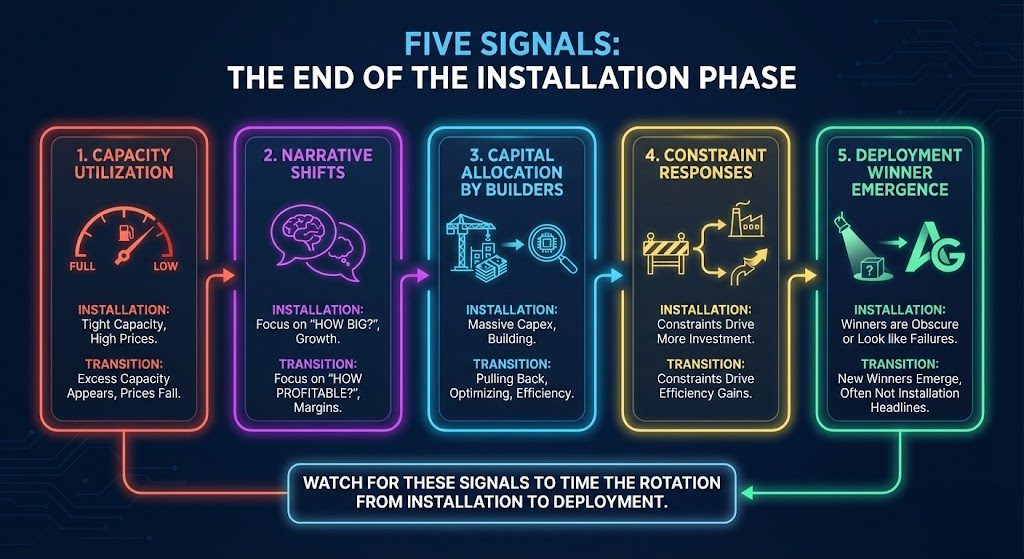

Five signals indicate when installation is ending:

First, capacity utilization. During installation, capacity is always tight. During transition, excess capacity appears. For AI, this shows up as declining GPU prices, falling inference costs, data centers below optimal utilization. As of late 2025, we're seeing the opposite. Capacity remains tight. Build-out is accelerating.

Second, narrative shifts. When companies stop emphasizing growth and start emphasizing profitability, when investors stop rewarding revenue multiples and start demanding margins, when conversation shifts from "how big" to "how profitable," the phase is changing. Right now the narrative is firmly installation. The focus is capacity, capability, scale.

Third, capital allocation by infrastructure builders. When Microsoft, Amazon, and Google pull back on data center construction, when they stop announcing massive capex programs, when they shift from building to optimizing, installation is ending. Through 2025, spending is accelerating. Anthropic just committed $50 billion. Stargate is racing toward $500 billion ahead of schedule.

Fourth, constraint responses. During installation, hitting constraints drives more infrastructure investment. During deployment transition, hitting constraints drives efficiency gains. Right now energy constraints are driving massive infrastructure investment in power generation, grid interconnects, and cooling. Classic installation behavior.

Fifth, deployment winner emergence. These companies might be obscure now. Amazon looked like a failing retailer in 2001. Google was a search engine with unclear monetization in 2002. Facebook didn't exist until 2004, well into internet deployment. The winners often aren't the companies dominating installation headlines.

Based on these signals, AI installation likely has room to run. But uncertainty about timing doesn't mean uncertainty about sequence. The phases will play out. The rotation will come.

Why organizations struggle to transition

There's a deeper reason phases reward different companies. Installation success requires organizational capabilities that become liabilities during deployment.

Installation winners optimize for speed over efficiency, market share over profitability, vision over execution. These characteristics are adaptive when building capacity fast is paramount. They become destructive when the game shifts to extracting margins from capacity that exists.

Deployment winners optimize for capital efficiency, operational excellence, and sustainable unit economics. These characteristics look conservative during installation. They become adaptive when profitability matters.

This is why you see leadership turnover between phases. The companies that dominated railway installation weren't the railways that dominated deployment. Electrical infrastructure builders weren't the companies that profited most from electrification. Internet infrastructure providers from the 1990s weren't the platform companies that dominated the 2010s.

Some companies manage the transition. Amazon and Microsoft evolved as phases shifted. But they're remarkable exceptions. The organizational DNA, incentive structures, and skill sets required for each phase are so different that most companies can't transform.

This has direct implications for portfolio construction. You can't simply buy installation winners and hold through deployment expecting similar returns. The companies need to fundamentally change, and most can't.

Portfolio construction across phases

For long-term allocators, the solution isn't avoiding installation phase investments. Installation returns can be extraordinary. The solution is understanding what you own, why you own it, and having a framework for rotation.

Right now, late 2025, own infrastructure with eyes open. Own Nvidia understanding it's an installation trade on sustained build-out and pricing power, not a bet on long-term position in mature AI infrastructure. Own neo-clouds understanding it's a bet on temporary arbitrage in specialized compute, not a bet they become the AWS of AI. Own hyperscalers understanding their massive capex programs eventually end and growth rates normalize.

But build the watch list for deployment. Companies in traditional industries positioned to use AI for transformational cost reduction or capability enhancement. Application layer companies building AI-native products for specific workflows. Businesses with proprietary data or network effects that become more valuable in an AI-enabled world.

These probably look boring today. A regional bank using AI to improve credit decisioning. A trucking company using AI to optimize fleet management. A pharmaceutical company using AI to accelerate drug discovery. Not headline stories. Operational stories. The kind that compound quietly during deployment while everyone watches infrastructure stocks mean revert.

The timing of rotation is genuinely uncertain. But the necessity of rotation is not. And the cost of mistiming by staying too long in installation trades exceeds the cost of rotating slightly early.

Perez calls deployment the "golden age" of a technological revolution, when productivity gains diffuse through the economy and living standards rise. It's also when investment returns shift from spectacular and concentrated to steady and broad. Installation captures attention. Deployment captures value.

The non-consensus positioning

Most institutional investors will follow the consensus path. They'll own infrastructure heavily during the build-out, hold too long through the turning point, and rotate to deployment winners only after the opportunity is obvious and priced in.

The non-consensus positioning is accepting lower returns during peak installation in exchange for better positioning for the full cycle. This means starting to build deployment exposure before it's obvious, even while installation continues. It means recognizing that the spectacular returns from infrastructure trades come with spectacular risk of giving those returns back.

It means understanding that when Nvidia has compounded 10x, the next 10x is far less likely than the first. When neo-clouds are trading at massive premiums to AWS on specialized AI compute, those premiums are vulnerable to competition and commoditization. When hyperscaler capex reaches unprecedented levels, those levels are unsustainable and will normalize.

And it means watching for companies that are building deployment advantages while everyone focuses on installation. The healthcare company quietly integrating AI into diagnostic workflows. The logistics company restructuring operations around AI-optimized routing. The financial services firm retraining underwriters on AI-augmented processes.

These companies won't have the price momentum of installation winners. They'll compound slowly and steadily. And over the full cycle, they'll likely generate better risk-adjusted returns than the infrastructure trades that dominated headlines during installation.

Traders win during installation. Operators win during deployment. Right now we're still in installation, and the traders are winning. But the operators are building positions, and their time is coming.

The question is which phase you're investing in, whether your portfolio matches that phase, and whether you have a plan for rotation when the phase shifts.

Because it will shift. It always does.